This starts with a simple puzzle. You won’t need a pencil, much less a calculator, and it will help strengthen your probabilistic intuition, so do try to work this one out.

The Premises

Premise 1:

I have a bag of at least 1 but no more than 100 numbered tiles.

Premise 2:

The tiles are sequentially numbered. Numbers start at 1, and no numbers are skipped, so a bag of 72 such tiles would contain tiles numbered…

Premise 3:

I reach into the bag, randomly select one of the numbered tiles, show it to you, and place it back in the bag. The tile is number 5.

The Question

How many tiles are in my bag?

If you don’t know the answer, take just a minute to think it through. While you’re thinking (and to give a little vertical space), here’s a brief eulogy for the Big Foot. ;e

A Brief Eulogy for the Big Foot

In 1980, Mt. St. Helens in Washington State erupted for the first time in 120 years, blowing volcanic gasses and super-heated ash 15 miles into the atmosphere (commercial airliners fly at around 5 miles up). The eruption destroyed hundreds of square miles of wilderness, killing 57 human beings and many thousands of animals.

I was 6 years old.

Perhaps five years later, I came across a magazine article on Big Foot, the mysterious, hirsute hominin rumored at the time to be hiding in untamed portions of the US Pacific Northwest. Now, the idea is ridiculous, but at the time, Big Foot was at least a lot of fun to consider. Satellite photography was poor, and portable cameras were large, fragile, expensive, and rare. There was more room then for the unknown.

But not all of us believed. Positions on Big Foot were cleanly divided between

- the incidentally-true-but-meaningless, “There is no proof”; and

- the equally true, equally meaningless, “Yeah, but absence of evidence is not evidence of absence.”

Like most kids, I took the latter position. I believed in Big Foot the way I believed in giant squid—and (remember, this was the 80s) I’d never seen a clear photo of either.

But the article made a compelling point: no dead Big Feet were found after the Mt. St. Helens eruption. That fact wasn’t easy to dismiss. If Big Feet lived on Mt. St. Helens, they should have died on Mt. St. Helens. This was evidence that shouldn’t have been absent. This is when I lost my belief. Big Foot died in 1980 (RIP), even if it took me five years to figure it out.

It was a sad day for mythical hominini, but an important early lesson in probability: When you can’t answer a question, question an answer.

Was that a hint?

To review, I have a bag with somewhere between 1 and 100 consecutively numbered tiles. I reach into the bag and randomly select one of the tiles. The tile is number 5. How many tiles are in the bag?

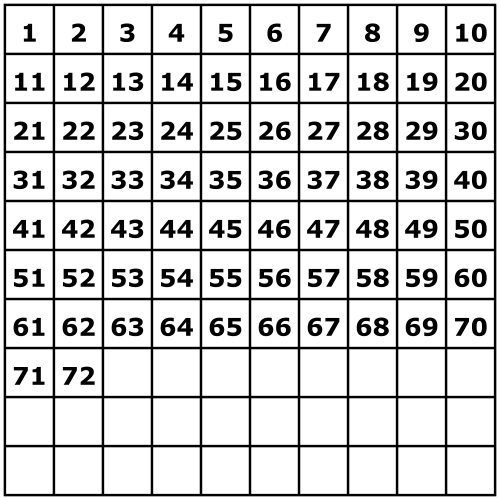

We know there are at least 5, but we can’t “rule out” any number between 5 and 100. So where do we go from here?

Let’s start with how we know there are at least 5. We know there are at least 5 tiles in the bag, because if there were only 1, 2, 3, or 4, there would not be a tile number 5. See what we did? We questioned an answer—four answers, in fact.

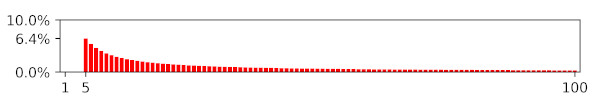

Here it is on a particularly boring graph.

\(n\in[1..4]\)

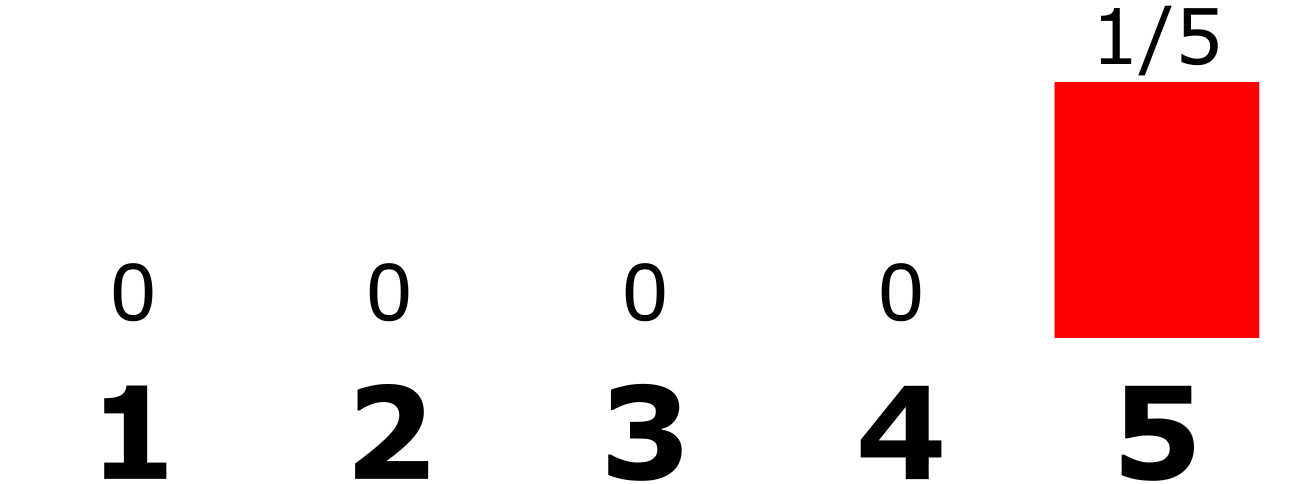

Now let’s look at one of the possible answers. If there were 5 tiles in the bag, we’d have a 1-in-5 chance of drawing the number 5 tile. Let’s add that to our graph.

\(n\in[1..5]\)

5 is clearly a better candidate than 1, 2, 3, or 4, but is it the best candidate? Let’s try a few more.

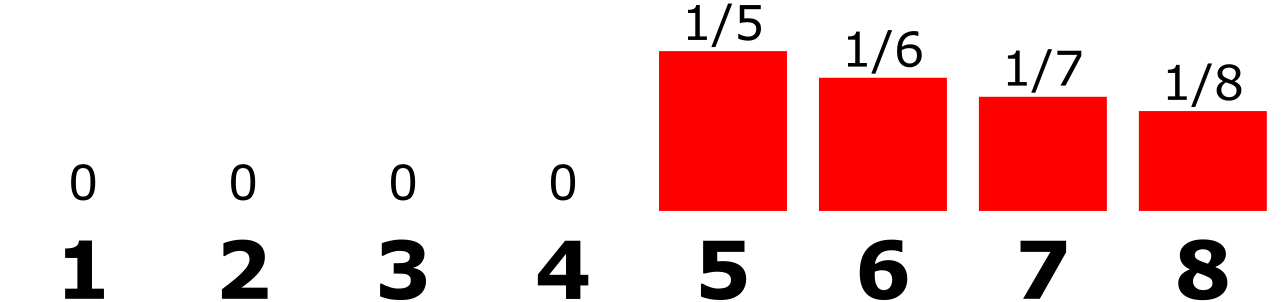

\(n\in[1..8]\)

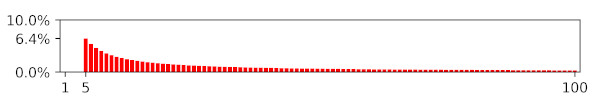

The trend here is obvious. We will never see a better candidate than five.

\(n\in[1..100]\)

So the best answer is…

When you select the \(n^{\text{th}}\) tile from a bag of tiles, the best guess for the number of tiles in the bag is \(n\).

The percentages will change, but \(n\) will always be the most likely choice, whatever tile I show you and however many tiles might be in the bag.

Does that sound wrong?

That’s because it usually is.

Right More

\(n\) is the right answer when you have to have the right answer. If you guess \(n\) (with a maximum of 100 tiles), you’ll be exactly right around 5.2% of the time and exactly wrong the rest. If you want to be right more often, guess \(n\).

Less Wrong

But how often do we have to be exactly right? And how often do we get to be exactly wrong for free?

Instead of numbered tiles, let’s imagine sequentially numbered military tanks, somewhere between 1 and 100 of them. You see one tank, number 5, and you now have to organize an opposing force with limited resources. Too little opposition is bad. Too much opposition is bad. Will you still assume there are only 5 tanks?

As far as I know, only magicians and leprechauns will ever approach you with a bag of mysterious numbered tiles, but the tank scenario actually occurred.

Let’s model the tank scenario

We’ll model the tank scenario with our bag of tiles. Everything else remains the same, except that now, you’ll have to pay if you’re wrong, and the more wrong you are, the more you’ll have to pay. For example, if you guess 5 and the answer is 7 or 3, you’ll pay two dollars for missing by two. If the answer is 8 or 2, you’ll pay three dollars for missing by three.

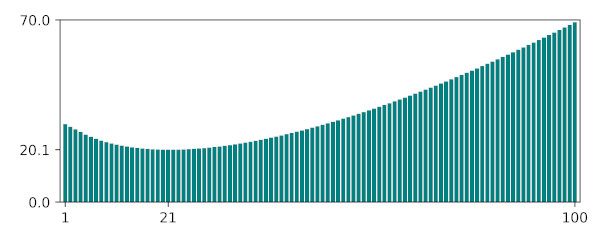

This is a little more math. Starting from this chart we’ve already seen, we have to look at every combination of guess and truth.

\(n\in[1..100]\)

If we guess 5:

- there is a 6.4% chance we are correct, so penalty would be 0.

- there is a 5.2% chance of 6 tiles in the bag, so 5.2% chance penalty = 1

- there is a 4.6% chance of 7 tiles in the bag, so 4.6% chance penalty = 2

- …

- there is a 0.3% chance of 100 tiles in the bag, so 0.3% chance penalty = 95

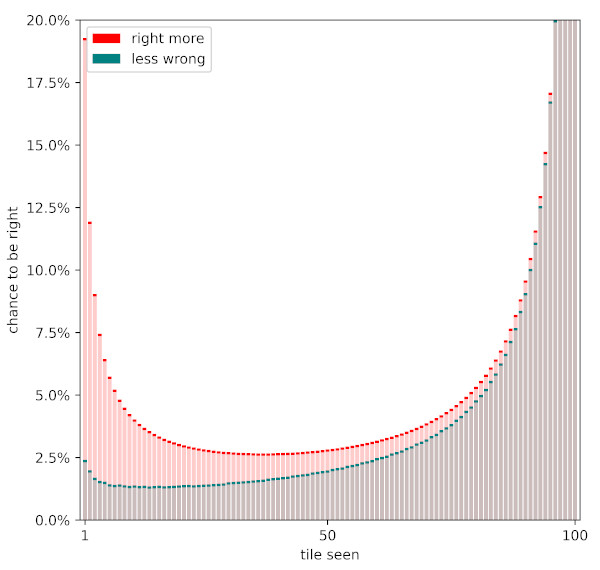

Repeat that for every guess, and we end up here.

Look closely. There is a probability mini-lesson in the fact that the sure losers (1 through 4) have a better expected return than many of the possible winners.

Following the “Less Wrong” strategy, the best guess (having seen tile 5) is 21.

Do you want to be right more or less wrong?

We have two strategies, “right more” and “less wrong”. Right more is right more than less wrong (5.2% for right more vs. 1.9% for less wrong) and less wrong is less wrong than right more ($16.81 for less wrong vs. $24.75 for right more).

But that’s not all you know, or need to know! Those numbers change once the random tile is revealed.

You could devise many hybrid strategies to balance right and wrong. But don’t get in a hurry, remember that you’ll see some tiles more than others (there’s a 1 tile in every bag). When you get that far, devise a strategy for having seen two tiles. Then three. There’s more than one answer for those too.

Whether you want to be more right or less wrong, the numbers are on your side. But they’re on my side too!

The Takeaway

Math will give you the answer to an equation, but it will rarely give you the answer to a problem. And the more math you know, the more (competing) answers you’ll find. Winning doesn’t always mean you’re not losing, and losing doesn’t always mean you’re wrong. Be wary of certainty, even when you have “the evidence”.